Go To Section

Launceston (Dunheved)

Borough

Available from Boydell and Brewer

Elections

| Date | Candidate |

|---|---|

| 1386 | John Cokeworthy I |

| Roger Leye | |

| 1388 (Feb.) | John Cokeworthy I |

| William Bodrugan I | |

| 1388 (Sept.) | Thomas Trereise |

| Thomas Treuref | |

| 1390 (Jan.) | John Cokeworthy I |

| John Syreston | |

| 1390 (Nov.) | |

| 1391 | John Cokeworthy I |

| Richard Lovyn | |

| 1393 | John Cokeworthy I |

| Richard Lovyn | |

| 1394 | |

| 1395 | John Cokeworthy I |

| Richard Lovyn | |

| 1397 (Jan.) | John Cokeworthy I |

| Richard Tolle | |

| 1397 (Sept.) | Roger Menwenick |

| William Holt I | |

| 1399 | John Cokeworthy I |

| John Goly | |

| 1401 | |

| 1402 | Thomas Colyn |

| Richard Raddow | |

| 1404 (Jan.) | |

| 1404 (Oct.) | |

| 1406 | Walter Tregarya |

| John Colet | |

| 1407 | Richard Brackish |

| ?John Pengersick 1 | |

| 1410 | Edward Burnebury |

| John Cory | |

| 1411 | Edward Burnebury |

| Richard Trelawny | |

| 1413 (Feb.) | |

| 1413 (May) | Edward Burnebury |

| John Mayhew I | |

| 1414 (Apr.) | |

| 1414 (Nov.) | Edward Burnebury |

| John Cory | |

| 1415 | |

| 1416 (Mar.) | Oliver Wyse |

| John Palmer III | |

| 1416 (Oct.) | |

| 1417 | Edward Burnebury |

| John Cory | |

| 1419 | Edward Burnebury |

| John Palmer III | |

| 1420 | Simon Yurle |

| John Palmer III | |

| 1421 (May) | Simon Yurle |

| John Cory | |

| 1421 (Dec.) | John Treffridowe |

| John Palmer III |

Main Article

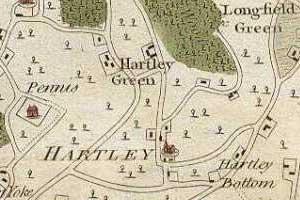

By the later Middle Ages three separate townships had grown up at Launceston: Launceston ‘St. Stephen’, Dunheved and Newport. Each of the three at various times adopted the name of ‘Launceston’, and confusion between them increased after 1529 when both Newport and Dunheved returned Members to Parliament, for Newport made returns as ‘Launceston’ and Dunheved (which until then had generally done the same) took to using its ancient name. However, in the 14th and early 15th centuries Newport was of minor importance, and the histories of the other two townships may be easily disentangled. Dunheved started as a settlement planted by Robert, count of Mortain, soon after the Norman Conquest. The count constructed a castle on the commanding hilltop across the river Kensey from the Saxon town of Launceston St. Stephen (founded by the monks of St. Stephens priory). Not only that: some time before 1086 he moved the market from the older town to his new one. The priory town is said to have subsequently decayed, yet in 1377 it contained 420 adults who contributed to the poll tax, while Dunheved had only 302. The medieval parliamentary borough may, therefore, have had a total population of no more than 500.2 But other factors gave Dunheved an importance greater than its size suggests: Launceston was the ‘strategic key of the peninsula’, guarding the approaches to Cornwall, and the castle at Dunheved was not only considered to be worth keeping in good repair, but was occasionally (in 1369 for example) even brought up to full garrison strength. Then, too, within the castle was ‘a hawle for syses and sessions’ and ‘a commune gayle [gaol] for al Cornwayle’ (Leland). The emergence of the place as the judicial centre for the shire stemmed from its creation in the 11th century as the head of the honour of Launceston, an honour which embraced all the lesser honours of the Mortain fief; so it was there that was exercised the jurisdiction of the ‘court of the gate of the castle’ (which also applied to certain tenants of the duchy of Cornwall). But more important still in the later Middle Ages were the county assizes. These were usually held at Dunheved, but since the town was only two miles from the Devon border this was very inconvenient for most men of the county, few of whom could make the journey within a day, and it was probably for this reason that assizes were held at Lostwithiel in 1317-18, at Bodmin in 1310-11 and 1330-1, and at Lostwithiel again in the 1380s. In order to protect their interests, the burgesses of Dunheved, whose trade must have benefited greatly from the custom brought by the courts, sent a petition to Richard II to obtain formal confirmation that sessions should be held in their town, and not elsewhere. The privilege was contained in a charter dated 16 Oct. 1386 (granted during the first Parliament of our period).3

From its beginnings Dunheved belonged to the earls of Cornwall and then to the dukes. The borough owed its earliest charter to Richard, earl of Cornwall, Henry III’s brother. At some point between 1227 and 1242 he granted the burgesses various liberties, including the right to elect their own portreeves, to answer for the fee farm of the borough, to try their own pleas (with the usual exceptions) and to determine the assizes of bread and ale. The same earl also assigned to the burgesses a plot of land within the town walls where they could erect a guildhall, and in another charter allowed them to hold an annual fair. In return for these concessions, the inhabitants were expected to pay certain dues, which remained fixed throughout the medieval period. The annual fee farm amounted to no more than £5, and the rent payable for the site of the guildhall was only one pound of pepper, worth 12d. But as well as these payments the townspeople were annually required to expend certain other sums on their lord’s behalf: £3 5s.10d. to Launceston priory for the maintenance of a chantry and for a lamp to be kept burning near the statue of the Virgin, and £5 to the leper-house at Gillemartin. In 1355 the Black Prince notified his ministers that, like the burgesses of all other Cornish boroughs appurtenant to the duchy, those of Dunheved were to be exempted from all tolls including picage, passage, murage and pannage throughout the realm, so extending a privilege which, granted them a century earlier, had then applied only to the estates of the earldom of Cornwall.4 Dunheved’s charters were confirmed by Richard II in May 1383, but evidently some question then arose about their precise content or meaning, and in October commissioners were sent to Cornwall to investigate. At the hearing a local jury testified that borough courts were held every Monday for all cases touching the burgesses; that no sheriff, bailiff or other minister of the King or duke might enter the borough in order to requisition goods, make distraint on property or arrest any person, except in the presence and with the consent of the mayor; that there was a merchant guild; that markets were held on Tuesdays and Saturdays, and an annual fair in Whit week; and that the burgesses were entitled to certain dues collected at the St. German’s fair and on the ferries over the Tamar. No curtailment of the borough’s liberties resulted from the inquiries, and the charters were confirmed in their entirety by Henry IV and Henry V.5

It is clear from the evidence sent to Chancery in 1383 that the internal government of Dunheved was left almost entirely in the hands of the burgesses, a group probably corresponding with the guild merchant. Since the mid 13th century the chief officer had been known by the title of ‘mayor’. In 1319 there had been disputes among the townspeople regarding the electoral procedure for the mayoralty, the outcome of which was a resolution that henceforth the eight aldermen of the borough and 12 burgesses of the better, more worthy sort, should elect, and that if they were unable to reach a decision the mayor was to be chosen from among the aldermen by the aldermen themselves with the help of only four of the 12 burgesses. The mayor-elect evidently had to be approved by all the burgesses, for in 1383 it was held that, in order that they might maintain the borough’s liberties, levy rents and answer to the King or the duke of Cornwall for the fee farm, he and the two portreeves should be elected ‘by common assent’. It is uncertain at what time of the year local elections were customarily held, but the official year generally began on the feast of St. Katherine the Virgin (25 Nov.). Grants and leases of communal property were made jointly by the mayor and the eight aldermen. By 1432 there were several lesser officials, including a steward and a keeper of ‘le clok’, who assisted in the administration of the town. Dunheved seems also to have sought and paid for legal counsel on an ad hoc basis until the mid 15th century. Certainly, no mention of a recorder has been found before 1460 (when Edward Aysshton† occupied the post).6

Dunheved had made returns to Parliament regularly since 1295. Parliamentary elections were probably held in the town, but whether the franchise extended to the whole body of burgesses or (as in the mayoral elections) was limited to a select few, is not known. The surviving borough accounts show that the elections of 1467 were held at the guildhall, and this may well have been the practice in earlier times. In Cornwall the venue of county courts and, therefore, the place where the shire elections were to be held, was a subject of contention during the 14th century. One of the provisions of Dunheved’s first charter stipulated that eight county courts were to be held there every year, but, so the burgesses complained in 1337, Earl Richard (d.1272) had moved the courts to Bodmin, and Earl Edmund (d.1300) had transferred them to Lostwithiel, where they had been held ever since. In 1383 it was said that only three county courts were being held at Dunheved annually instead of the eight allowed by charter. Consequently, in the late 14th and early 15th centuries the majority of parliamentary elections for the shire were held at Lostwithiel. In November 1414, even though the sheriff was at Dunheved when he received the parliamentary writ, he nevertheless ordered the electors to meet in the other town. However, the practice appears to have gradually changed in Dunheved’s favour during the course of the century, for elections came to be held at the castle more frequently (certainly in 1411, 1419, 1422, 1432, 1442, 1447 and 1449).7

The names of the parliamentary burgesses for Dunheved are known for only 23 of the 32 Parliaments convened between 1386 and 1421, missing or damaged returns leaving gaps for the assemblies of 1390 (Nov.), 1394, 1401, 1404, 1413 (Feb.), 1414 (Apr.), 1415 and 1416 (Oct.). As many as 19 of the 25 men known to have represented this borough were, so far as surviving evidence goes, returned by Dunheved to only one Parliament. But a few made up for the seeming reluctance of the majority: Simon Yurle sat in five Parliaments between 1420 and 1429, John Cory in six between 1410 and 1423, Edward Burnebury in seven between 1410 and 1422, and John Palmer III in 11 between 1416 and 1435. Even Palmer’s record failed to match that of John Cokeworthy I, who had sat in no fewer than 17 Parliaments between 1377 and 1399 for Dunheved alone, and in addition had been returned by Lostwithiel once and by Liskeard three times in the same period; in fact, he only missed two of Richard II’s Parliaments for which returns have survived. It should also be noted that certain of the men who represented Dunheved only once had been returned on previous occasions by other Cornish boroughs: thus William Bodrugan I and John Pengersick had sat for Helston; John Goly and John Treffridowe for Helston and Liskeard; and John Syreston for Truro, Bodmin, Lostwithiel and Liskeard. Taking such experience of the Commons into account, it is evident that in no fewer than ten of the 23 Parliaments for which returns have survived both of Dunheved’s representatives were tried men, and in seven more one of the Members had sat previously. Nevertheless, in six Parliaments (1388 (Sept.), 1397 (Sept.), 1402, 1406, 1410 and 1416 (Mar.)), if appearances are anything to go by, the borough was represented by two novices. (The gaps in the returns, however, made this unlikely in at least the last four instances). Re-election occurred quite frequently: on no fewer than seven occasions (in 1386, 1388 (Feb.), 1397 (Jan.), 1411, 1419, 1420 and 1421 (May)) one of the burgesses had sat in the Parliament immediately preceding; and both Members in the Commons of 1391 were re-elected in 1393). Indeed, the impression is that Dunheved set some store by parliamentary experience, and favoured tried men as candidates. Thus Cokeworthy was sent to all but two of the ten Parliaments convened between 1386 and 1399 for which returns have survived; and Edward Burnebury was elected to six of the seven Parliaments so recorded between 1410 and 1419; while one experienced pair, Cokeworthy and Richard Lovyn, was returned in 1391, 1393 and 1395, and another, that of Burnebury and John Cory, in 1410, 1414 (Nov.), 1417 and 1422.

Local records have not survived in sufficient quantity or variety to establish with adequate precision what proportion of the 25 Members of this period usually lived in Dunheved. However, there are grounds for believing that certainly seven and possibly five more (John Colet, John Goly, Roger Leye, Richard Raddow and Thomas Trereise, none of whom have been satisfactorily identified) were townsmen in the strict sense. Of the remainder, 11 were Cornishmen, some of them (like Oliver Wyse, Richard Trelawny and Roger Menwenick) living within at least a few miles of Dunheved and even, as in Wyse’s case, owing property there. That two of the parliamentary burgesses (Walter Tregarya and William Holt I) in all probability lived in Devon, and that others (such as John Cokeworthy I, John Palmer III and Oliver Wyse) had landed interests east of the Tamar, is scarcely surprising in view of Dunheved’s proximity to the border; and too little is known about Tregarya and Holt to call them ‘outsiders’ with conviction. It is also, and for the same general reasons, difficult to establish how many of Dunheved’s MPs were local tradesmen. Certainly, more than a third of the total were known as ‘gentlemen’ or ‘esquires’, and these all had substantial landed holdings in Cornwall. For example, William Bodrugan I, although illegitimate, was acknowledged to belong to one of the most important families of the shire; and Oliver Wyse’s income from land amounted to nearly £40 a year. Nor can there be much doubt that the burgesses of Dunheved preferred to elect members of the legal profession rather than tradesmen like themselves. Although only five of the 25 MPs have been positively identified as lawyers, those five included men with outstanding parliamentary records, like Cokeworthy and Burnebury, and clearly dominated the representation of the borough. In only five of the 23 Parliaments for which returns have survived (1388 (Sept.), 1397 (Sept.), 1402, 1406 and 1407) was neither of the MPs a man of law. Willingness on the part of the lawyers to undertake the arduous journey to Westminster may be explained by their concern for their practices in the central courts. For example, the representatives in the Parliaments of 1380 (Jan.), 1381, 1382 (Oct.) and 1385 (John Bodilly* and John Cokeworthy I in every instance) were both of them attorneys in the King’s bench. Indeed, Bodilly, being keeper of the court’s rolls, must have been obliged to spend all the law terms at Westminster. From the borough’s point of view the lawyers’ readiness to combine attendance in the Commons with appearances in the courts on behalf of their clients had one important additional advantage: it provided the opportunity to reduce expenditure. There is evidence that later on the burgesses of Dunheved were reluctant to pay their Members more than a purely nominal sum: for their parliamentary services in 1432 John Palmer III and Nicholas Aysshton* received only half a mark apiece (and this was for attendance at a Parliament which lasted over two months); each of the representatives in the longer Parliament of 1449-50 was paid a flat sum of 20s., and in that of 1450-1 a mark (13s.4d.); and in 1459 a single mark again sufficed for both.8

Only three of the 25 MPs are known to have ever held office as mayor of Dunheved: John Cory, John Mayhew I and John Palmer III. Admittedly, Palmer was probably mayor when elected in 1429 and 1433 (his seventh and tenth appearances), but, clearly, experience of mayoral functions was not important in achieving success at the hustings. The same was true of posts in the duchy and of crown appointments. None of the Members for Dunheved ever held the most prestigious duchy office in the locality, that of constable of its castle. And although four occupied other duchy offices (William Bodrugan I served as sheriff, John Goly as bailiff of Foweymore, John Mayhew I as deputy feodary and John Treffridowe as joint havener of some of the Cornish ports), and another, Edward Burnebury, was even involved in the duchy administration on a high level (as an official responsible for arranging leases), only in one case is it at all likely that parliamentary service coincided with occupancy of a duchy office: Mayhew may well have been appointed as John Hawley II’s* deputy in the feodary’s office before his election to Henry V’s first Parliament. Seven parliamentary burgesses filled various posts in the Crown’s appointment, either in Cornwall or Devon: Edward Burnebury, Thomas Colyn, John Palmer III and Oliver Wyse all served as coroners; John Syreston as escheator and alnager; John Cory as a controller and collector of customs; and William Holt I as a searcher, alnager and customer. But only in the cases of Colyn (who was a coroner in Cornwall when elected in 1402) and Cory (who was controller of customs of Plymouth and Fowey when elected in 1421, 1422 and 1423) did parliamentary service come within their term of office. So far as Cory is concerned, he had been returned to three Parliaments before discharging royal office, which suggests that his promotion can hardly have crucially influenced the electors’ decision. Eight Members were at one time or another put on royal commissions serving in Devon and Cornwall, but none was ever appointed as a j.p.

By the later Middle Ages three separate townships had grown up at Launceston: Launceston ‘St. Stephen’, Dunheved and Newport. Each of the three at various times adopted the name of ‘Launceston’, and confusion between them increased after 1529 when both Newport and Dunheved returned Members to Parliament, for Newport made returns as ‘Launceston’ and Dunheved (which until then had generally done the same) took to using its ancient name. However, in the 14th and early 15th centuries Newport was of minor importance, and the histories of the other two townships may be easily disentangled. Dunheved started as a settlement planted by Robert, count of Mortain, soon after the Norman Conquest. The count constructed a castle on the commanding hilltop across the river Kensey from the Saxon town of Launceston St. Stephen (founded by the monks of St. Stephens priory). Not only that: some time before 1086 he moved the market from the older town to his new one. The priory town is said to have subsequently decayed, yet in 1377 it contained 420 adults who contributed to the poll tax, while Dunheved had only 302. The medieval parliamentary borough may, therefore, have had a total population of no more than 500.9 But other factors gave Dunheved an importance greater than its size suggests: Launceston was the ‘strategic key of the peninsula’, guarding the approaches to Cornwall, and the castle at Dunheved was not only considered to be worth keeping in good repair, but was occasionally (in 1369 for example) even brought up to full garrison strength. Then, too, within the castle was ‘a hawle for syses and sessions’ and ‘a commune gayle [gaol] for al Cornwayle’ (Leland). The emergence of the place as the judicial centre for the shire stemmed from its creation in the 11th century as the head of the honour of Launceston, an honour which embraced all the lesser honours of the Mortain fief; so it was there that was exercised the jurisdiction of the ‘court of the gate of the castle’ (which also applied to certain tenants of the duchy of Cornwall). But more important still in the later Middle Ages were the county assizes. These were usually held at Dunheved, but since the town was only two miles from the Devon border this was very inconvenient for most men of the county, few of whom could make the journey within a day, and it was probably for this reason that assizes were held at Lostwithiel in 1317-18, at Bodmin in 1310-11 and 1330-1, and at Lostwithiel again in the 1380s. In order to protect their interests, the burgesses of Dunheved, whose trade must have benefited greatly from the custom brought by the courts, sent a petition to Richard II to obtain formal confirmation that sessions should be held in their town, and not elsewhere. The privilege was contained in a charter dated 16 Oct. 1386 (granted during the first Parliament of our period).10

From its beginnings Dunheved belonged to the earls of Cornwall and then to the dukes. The borough owed its earliest charter to Richard, earl of Cornwall, Henry III’s brother. At some point between 1227 and 1242 he granted the burgesses various liberties, including the right to elect their own portreeves, to answer for the fee farm of the borough, to try their own pleas (with the usual exceptions) and to determine the assizes of bread and ale. The same earl also assigned to the burgesses a plot of land within the town walls where they could erect a guildhall, and in another charter allowed them to hold an annual fair. In return for these concessions, the inhabitants were expected to pay certain dues, which remained fixed throughout the medieval period. The annual fee farm amounted to no more than £5, and the rent payable for the site of the guildhall was only one pound of pepper, worth 12d. But as well as these payments the townspeople were annually required to expend certain other sums on their lord’s behalf: £3 5s.10d. to Launceston priory for the maintenance of a chantry and for a lamp to be kept burning near the statue of the Virgin, and £5 to the leper-house at Gillemartin. In 1355 the Black Prince notified his ministers that, like the burgesses of all other Cornish boroughs appurtenant to the duchy, those of Dunheved were to be exempted from all tolls including picage, passage, murage and pannage throughout the realm, so extending a privilege which, granted them a century earlier, had then applied only to the estates of the earldom of Cornwall.11 Dunheved’s charters were confirmed by Richard II in May 1383, but evidently some question then arose about their precise content or meaning, and in October commissioners were sent to Cornwall to investigate. At the hearing a local jury testified that borough courts were held every Monday for all cases touching the burgesses; that no sheriff, bailiff or other minister of the King or duke might enter the borough in order to requisition goods, make distraint on property or arrest any person, except in the presence and with the consent of the mayor; that there was a merchant guild; that markets were held on Tuesdays and Saturdays, and an annual fair in Whit week; and that the burgesses were entitled to certain dues collected at the St. German’s fair and on the ferries over the Tamar. No curtailment of the borough’s liberties resulted from the inquiries, and the charters were confirmed in their entirety by Henry IV and Henry V.12

It is clear from the evidence sent to Chancery in 1383 that the internal government of Dunheved was left almost entirely in the hands of the burgesses, a group probably corresponding with the guild merchant. Since the mid 13th century the chief officer had been known by the title of ‘mayor’. In 1319 there had been disputes among the townspeople regarding the electoral procedure for the mayoralty, the outcome of which was a resolution that henceforth the eight aldermen of the borough and 12 burgesses of the better, more worthy sort, should elect, and that if they were unable to reach a decision the mayor was to be chosen from among the aldermen by the aldermen themselves with the help of only four of the 12 burgesses. The mayor-elect evidently had to be approved by all the burgesses, for in 1383 it was held that, in order that they might maintain the borough’s liberties, levy rents and answer to the King or the duke of Cornwall for the fee farm, he and the two portreeves should be elected ‘by common assent’. It is uncertain at what time of the year local elections were customarily held, but the official year generally began on the feast of St. Katherine the Virgin (25 Nov.). Grants and leases of communal property were made jointly by the mayor and the eight aldermen. By 1432 there were several lesser officials, including a steward and a keeper of ‘le clok’, who assisted in the administration of the town. Dunheved seems also to have sought and paid for legal counsel on an ad hoc basis until the mid 15th century. Certainly, no mention of a recorder has been found before 1460 (when Edward Aysshton† occupied the post).13

Dunheved had made returns to Parliament regularly since 1295. Parliamentary elections were probably held in the town, but whether the franchise extended to the whole body of burgesses or (as in the mayoral elections) was limited to a select few, is not known. The surviving borough accounts show that the elections of 1467 were held at the guildhall, and this may well have been the practice in earlier times. In Cornwall the venue of county courts and, therefore, the place where the shire elections were to be held, was a subject of contention during the 14th century. One of the provisions of Dunheved’s first charter stipulated that eight county courts were to be held there every year, but, so the burgesses complained in 1337, Earl Richard (d.1272) had moved the courts to Bodmin, and Earl Edmund (d.1300) had transferred them to Lostwithiel, where they had been held ever since. In 1383 it was said that only three county courts were being held at Dunheved annually instead of the eight allowed by charter. Consequently, in the late 14th and early 15th centuries the majority of parliamentary elections for the shire were held at Lostwithiel. In November 1414, even though the sheriff was at Dunheved when he received the parliamentary writ, he nevertheless ordered the electors to meet in the other town. However, the practice appears to have gradually changed in Dunheved’s favour during the course of the century, for elections came to be held at the castle more frequently (certainly in 1411, 1419, 1422, 1432, 1442, 1447 and 1449).14

The names of the parliamentary burgesses for Dunheved are known for only 23 of the 32 Parliaments convened between 1386 and 1421, missing or damaged returns leaving gaps for the assemblies of 1390 (Nov.), 1394, 1401, 1404, 1413 (Feb.), 1414 (Apr.), 1415 and 1416 (Oct.). As many as 19 of the 25 men known to have represented this borough were, so far as surviving evidence goes, returned by Dunheved to only one Parliament. But a few made up for the seeming reluctance of the majority: Simon Yurle sat in five Parliaments between 1420 and 1429, John Cory in six between 1410 and 1423, Edward Burnebury in seven between 1410 and 1422, and John Palmer III in 11 between 1416 and 1435. Even Palmer’s record failed to match that of John Cokeworthy I, who had sat in no fewer than 17 Parliaments between 1377 and 1399 for Dunheved alone, and in addition had been returned by Lostwithiel once and by Liskeard three times in the same period; in fact, he only missed two of Richard II’s Parliaments for which returns have survived. It should also be noted that certain of the men who represented Dunheved only once had been returned on previous occasions by other Cornish boroughs: thus William Bodrugan I and John Pengersick had sat for Helston; John Goly and John Treffridowe for Helston and Liskeard; and John Syreston for Truro, Bodmin, Lostwithiel and Liskeard. Taking such experience of the Commons into account, it is evident that in no fewer than ten of the 23 Parliaments for which returns have survived both of Dunheved’s representatives were tried men, and in seven more one of the Members had sat previously. Nevertheless, in six Parliaments (1388 (Sept.), 1397 (Sept.), 1402, 1406, 1410 and 1416 (Mar.)), if appearances are anything to go by, the borough was represented by two novices. (The gaps in the returns, however, made this unlikely in at least the last four instances). Re-election occurred quite frequently: on no fewer than seven occasions (in 1386, 1388 (Feb.), 1397 (Jan.), 1411, 1419, 1420 and 1421 (May)) one of the burgesses had sat in the Parliament immediately preceding; and both Members in the Commons of 1391 were re-elected in 1393). Indeed, the impression is that Dunheved set some store by parliamentary experience, and favoured tried men as candidates. Thus Cokeworthy was sent to all but two of the ten Parliaments convened between 1386 and 1399 for which returns have survived; and Edward Burnebury was elected to six of the seven Parliaments so recorded between 1410 and 1419; while one experienced pair, Cokeworthy and Richard Lovyn, was returned in 1391, 1393 and 1395, and another, that of Burnebury and John Cory, in 1410, 1414 (Nov.), 1417 and 1422.

Local records have not survived in sufficient quantity or variety to establish with adequate precision what proportion of the 25 Members of this period usually lived in Dunheved. However, there are grounds for believing that certainly seven and possibly five more (John Colet, John Goly, Roger Leye, Richard Raddow and Thomas Trereise, none of whom have been satisfactorily identified) were townsmen in the strict sense. Of the remainder, 11 were Cornishmen, some of them (like Oliver Wyse, Richard Trelawny and Roger Menwenick) living within at least a few miles of Dunheved and even, as in Wyse’s case, owing property there. That two of the parliamentary burgesses (Walter Tregarya and William Holt I) in all probability lived in Devon, and that others (such as John Cokeworthy I, John Palmer III and Oliver Wyse) had landed interests east of the Tamar, is scarcely surprising in view of Dunheved’s proximity to the border; and too little is known about Tregarya and Holt to call them ‘outsiders’ with conviction. It is also, and for the same general reasons, difficult to establish how many of Dunheved’s MPs were local tradesmen. Certainly, more than a third of the total were known as ‘gentlemen’ or ‘esquires’, and these all had substantial landed holdings in Cornwall. For example, William Bodrugan I, although illegitimate, was acknowledged to belong to one of the most important families of the shire; and Oliver Wyse’s income from land amounted to nearly £40 a year. Nor can there be much doubt that the burgesses of Dunheved preferred to elect members of the legal profession rather than tradesmen like themselves. Although only five of the 25 MPs have been positively identified as lawyers, those five included men with outstanding parliamentary records, like Cokeworthy and Burnebury, and clearly dominated the representation of the borough. In only five of the 23 Parliaments for which returns have survived (1388 (Sept.), 1397 (Sept.), 1402, 1406 and 1407) was neither of the MPs a man of law. Willingness on the part of the lawyers to undertake the arduous journey to Westminster may be explained by their concern for their practices in the central courts. For example, the representatives in the Parliaments of 1380 (Jan.), 1381, 1382 (Oct.) and 1385 (John Bodilly* and John Cokeworthy I in every instance) were both of them attorneys in the King’s bench. Indeed, Bodilly, being keeper of the court’s rolls, must have been obliged to spend all the law terms at Westminster. From the borough’s point of view the lawyers’ readiness to combine attendance in the Commons with appearances in the courts on behalf of their clients had one important additional advantage: it provided the opportunity to reduce expenditure. There is evidence that later on the burgesses of Dunheved were reluctant to pay their Members more than a purely nominal sum: for their parliamentary services in 1432 John Palmer III and Nicholas Aysshton* received only half a mark apiece (and this was for attendance at a Parliament which lasted over two months); each of the representatives in the longer Parliament of 1449-50 was paid a flat sum of 20 s., and in that of 1450-1 a mark (13 s.4 d.); and in 1459 a single mark again sufficed for both.15

Only three of the 25 MPs are known to have ever held office as mayor of Dunheved: John Cory, John Mayhew I and John Palmer III. Admittedly, Palmer was probably mayor when elected in 1429 and 1433 (his seventh and tenth appearances), but, clearly, experience of mayoral functions was not important in achieving success at the hustings. The same was true of posts in the duchy and of crown appointments. None of the Members for Dunheved ever held the most prestigious duchy office in the locality, that of constable of its castle. And although four occupied other duchy offices (William Bodrugan I served as sheriff, John Goly as bailiff of Foweymore, John Mayhew I as deputy feodary and John Treffridowe as joint havener of some of the Cornish ports), and another, Edward Burnebury, was even involved in the duchy administration on a high level (as an official responsible for arranging leases), only in one case is it at all likely that parliamentary service coincided with occupancy of a duchy office: Mayhew may well have been appointed as John Hawley II’s* deputy in the feodary’s office before his election to Henry V’s first Parliament. Seven parliamentary burgesses filled various posts in the Crown’s appointment, either in Cornwall or Devon: Edward Burnebury, Thomas Colyn, John Palmer III and Oliver Wyse all served as coroners; John Syreston as escheator and alnager; John Cory as a controller and collector of customs; and William Holt I as a searcher, alnager and customer. But only in the cases of Colyn (who was a coroner in Cornwall when elected in 1402) and Cory (who was controller of customs of Plymouth and Fowey when elected in 1421, 1422 and 1423) did parliamentary service come within their term of office. So far as Cory is concerned, he had been returned to three Parliaments before discharging royal office, which suggests that his promotion can hardly have crucially influenced the electors’ decision. Eight Members were at one time or another put on royal commissions serving in Devon and Cornwall, but none was ever appointed as a j.p.

Author: L. S. Woodger

Notes

- 1. It is, however, uncertain whether Pengersick sat for Launceston or Truro, as the endorsement of the parliamentary writ in question (C219/10/4) has some curious features. After the list of MPs for Helston, Bodmin, Lostwithiel and Liskeard, written in the usual form, each pair having two mainpernors, there appears on this occasion, written in a different hand, the name of Richard Brackish (described ambiguously, as 'one of the burgesses for the above said borough'), with three mainpernors, followed by that of John Pengersick, similarly described, also with three. The second scribe evidently simply copied the wording used for Liskeard's second Member, and perhaps the correct interpretation of what he wrote is that Brackish and the first named of his mainpernors (John Bole) were elected by Launceston, and Pengersick and his first mainpernor were elected for Truro. Certainly, the biographical information relating to Brackish and Pengersick suggests that the former was a Dunheved man, and that the latter, who lived at Helston, is more likely to have had connexions with Truro than with the borough at the other end of the county.

- 2. R. and O.B. Peter, Hist. Launceston, 2-5, 9, 60; M.W. Beresford, New Towns, 401, 405; R. Inst. Cornw. Jnl. iv. 27-41.

- 3. C. Henderson, Essays, 20; Hist. King’s Works ed. Brown, Colvin and Taylor, ii. 693-4; Harl. Ch. E7; J. Leland, Itin. ed. Toulmin Smith, i. 325; Caption of Seisin (Devon and Cornw. Rec. Soc. n.s. xvii), pp. xxiii, 9; L. Elliott-Binns, Med. Cornw. 120-1; CChR, v. 304-5.

- 4. Peter, 68-76; Caption of Seisin, pp. xliii-xlv, 4; Reg. Black Prince ii. 81.

- 5. CIMisc. iv. 265; CPR, 1381-5, p. 263; 1399-1401, p. 334; 1413-16, p. 267.

- 6. Peter, 39, 76, 88, 100, 101, 106, 124, 136, 140, 148.

- 7. Ibid. 151; Caption of Seisin, pp. xliii-xlv; C219/10/6, 11/4, 12/3, 13/1, 14/3, 15/2, 4, 6, 7.

- 8. Peter, 124-5, 131, 134, 137, 142.

- 9. R. and O.B. Peter, Hist. Launceston, 2-5, 9, 60; M.W. Beresford, New Towns, 401, 405; R. Inst. Cornw. Jnl. iv. 27-41.

- 10. C. Henderson, Essays, 20; Hist. King’s Works ed. Brown, Colvin and Taylor, ii. 693-4; Harl. Ch. E7; J. Leland, Itin. ed. Toulmin Smith, i. 325; Caption of Seisin (Devon and Cornw. Rec. Soc. n.s. xvii), pp. xxiii, 9; L. Elliott-Binns, Med. Cornw. 120-1; CChR, v. 304-5.

- 11. Peter, 68-76; Caption of Seisin, pp. xliii-xlv, 4; Reg. Black Prince ii. 81.

- 12. CIMisc. iv. 265; CPR, 1381-5, p. 263; 1399-1401, p. 334; 1413-16, p. 267.

- 13. Peter, 39, 76, 88, 100, 101, 106, 124, 136, 140, 148.

- 14. Ibid. 151; Caption of Seisin, pp. xliii-xlv; C219/10/6, 11/4, 12/3, 13/1, 14/3, 15/2, 4, 6, 7.

- 15. Peter, 124-5, 131, 134, 137, 142.